Amateurfunk in Tibet

Robert Webster Ford: Out of this World

Aus der "Daily Mail" vom 2. und 31. Juli 1955

The business of finding “auspicious” days for journeys tends to make one more complication to travelling in Tibet. But since few people are ever in a hurry, they are rarely concerned at delaying departure.

Dodging the bad luck

After seeing the Dalai Lama it is not considered provident to delay the start beyond a certain limited period, and should the Lamas decide that there is no excellent day available during that period, the traveller leaves on a second-rate or “good” day, hoping for the best.

There are other ways round this as I later discovered in Chamdo when I had to send a portable radio transmitter and crew urgently to Tengko. The High Lama said he was sorry but there were no auspicious days in sight on the calendar except for one which would not give sufficient time for preparation. The journey would have to be postponed.

So a young Tibetan clerk was sent out on the one available “auspicious” day and ordered to ride out some miles out along the route, halt, and then return. The full caravan left a few days later, confident that the gods had been fooled.

By the time we had assembled the caravan, I found we had more than 100 mules, ponies and horses, a sundry collection of porters, Tibetan officials and their families, servants, cooks, and a party of 12 armed guards to protect us on the way.

It was an impressive sight as we at last we pulled out of Lhasa, after days of farewell parties, being showered with gifts, and receiving visitors wishing us a successful journey.

“One for the road”

I felt rather like an Oriental potentate, scattering handfuls of coins to crowds who lined the route to see us off - another Tibetan custom.

On the way we passed tents beside the road which had been erected by friends of the Tibetan officials who were in the caravan in order to give them a resounding send-off. It took the best part of two days before the last “one for the road” had been downed and the Tibetans caught up the train again.

Transport was our major problem in the weeks which followed. We were not taking our own pack animals the whole distance, and a fresh batch had to be hired each day en route or at most for three or four days at a time.

We would send envoys ahead to the next settlement, who would arrange fresh transport. For weeks we saw no trees, trudging slowly across a bare, windswept plain, occasionally traversing difficult patches of swampy ground, and picking our way through innumerable herds of grazing yaks.

This vast, north-eastern plain is inhabited almost solely by nomadic tribes who wander about the area with their yak herds, pitching their yak-skin tents where it suits them. We frequently shared their camps to save pitching our own, and I found them tough, jovial, and hospitable folk, not frightened by a camera.

Tea and biscuits

After nearly two weeks’ travelling we reached Nagghuka, a tiny, insignificant town - a village by English standards - which is nevertheless important as the principal trading station for the whole of Northern Tibet.

It was there that I made the mistake of shaving. The night prior to our departure it snowed steadily, leaving a thick carpet on the route. But for the whole of the next day we marched under a brilliant, cloudless sky, across a virgin field of snow.

When I woke the next day, my face was paralysed solid. I was unable to move a muscle without the skin cracking like thick parchment burnt to a cinder by the ultra-violet reflections off the snow.

At long last, beyond the lost horizon, after the gruelling 10-week march from Lhasa, we suddenly dropped down a ravine and came to Chamdo, a grey, drab-looking group of rammed-mud huts, huddled in a deep ravine at the confluence of two rivers.

At first sight, the whole town, which lies more than two miles above sea level, looked as if you could pick it up and transport it elsewhere on a decent-sized mule train.

We were met by an emissary sent out by the local governor. He had pitched a tent, brewed up some English tea, produced a tin of sweet biscuits, and went through the now familiar scarf routine before we continued down the valley into the town.

They had hardly recovered from the shock of witnessing the arrival of their first Westerner when they were further confused next morning as I left my house to call on the Governor.

The governor

I had arrived wearing a considerable growth of beard, but the next day as I set out towards the Governor’s house it was a more or less suave and very clean-shaven face which they saw.

Governor Lhalu turned out to be a pleasant man who held Cabinet rank and was one of the four Ministers who came next in rank in the Tibetan hierarchy beneath the Lama and the Regent. He made no secret of the fact that he was very concerned about the news that was sifting across the uninhabited frontier regions from China.

He was convinced that India was planning to help Tibet in the event of an invasion, but I was not able to bring him any such comforting reassurance from Lhasa. On more than one occasion, Lhalu told me: “We will fight through if we have to ...” But he was removed from his post before invasion came.

We set up the station in a house away from town, and started in earnest to uncrate the larger equipment to set up the permanent R/T station. It was a two storey affair and I was given the top-floor apartment. It never occurred to me at the time that this factor would play a part in months of interrogation and mental persuasion which I received in Chinese prisons.

The purpose of my transfer to Chamdo was twofold - to set up an official telegraph link which would keep the governor in permanent contact with Lhasa and to open a commercial cable telephone service.

I really did begin to feel like the world’s loneliest Briton about this time. The nearest European was two months’ riding away, and Chamdo was not exactly crammed with modern amenities.

During my 16 months’ stay in Chamdo, mail from the outside world came through rarely and erratically. If we were lucky, it arrived by courier from Lhasa about once a month. Usually we were not lucky.

Before long, in order to keep some little link with the world outside the mountain barriers, I had opened up Station AC4RF and spent off-duty hours on the air as an amateur “ham.”

Almost before I had finished my first transmission onto the blue there was a whole string of hams from England and Australia, the United States and South Africa literally lining up on the ether to “talk” with me.

My first calls

For years Tibet had been the great unknown challenge to amateur radio men throughout the world, and suddenly they found me on the air transmitting from a spot that wasn’t even marked up on most people’s home atlases.

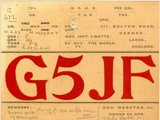

One of the first to establish contact with me was Station G5JF, which returned my call sign, gave his own, and then added as an afterthought ” ... from Burton-on-Trent, England.” I could hardly believe my pencil, which raced across the sheet turning the Morse into plain language.

Sitting there in my draughty hut, two miles up in the centre of Asia, and surrounded by 16,000 foot peaks, it didn’t seem possible that I was actually listening to somebody tapping his operating key in his warm bedroom probably a few streets from where my parents lived.

For the next few months Mr. Jeffries, the tailor - for that was who it was at the other end - kept me in fairly close touch with my parents, giving them news of me and sending messages from them. Since there was no other way I could have got news from them, I felt sure that the commercial authorities, who frown on such amateur “traffic”, would turn their faces the other way for once.

Not my job

In the spring of 1950 the vague rumblings of the Chinese army across the frozen frontier became distinctly more audible.

As I have said earlier, my original contract to set up radio links in the most distant corners of Tibet was in no way intended as an anti-invasion warning system, though it was difficult to persuade the Chinese of this. The fact remains that I was offered my contract as a Tibetan Civil servant in 1947.

Nevertheless there had always been British influence in Tibet since the days of Younghusband, and balancing this there had recently been a considerable increase in Chinese (K.M.T.) influence, which caused Tibetans to be mildly concerned about their eastern frontiers.

There was no clearly defined frontier but a vague, uninhabited, forbidding area where tribal rule held sway and where the local headman might or might not heed the interests of Lhasa.

Mystery tenant

News arrived slowly from the upper reaches of the Yangtse River, but scraps of news filtered back via traders and from the few Tibetan Army units that were scattered around the frontier area, pathetically thin on the ground.

On the Governor’s instructions, in May 1950 I sent out two of my Indian operators to set up a portable station at Tengko, on the Yangtse River frontier. The object of this move was to provide a link for the local authorities back to Chamdo, and ultimately to Lhasa. But the Indians were transmitting from there for hardly a month before they and the equipment were captured by advancing Chinese armies.

Meanwhile, a new tenant had arrived in the house outside Chamdo to take possession of the flat below mine. He was a Lama who had come from China and I saw very little of him. However, only two weeks after arriving, he died suddenly under circumstances of some mystery. It was thought he may have been poisoned, but I never dreamed at that time that I would be accused of poisoning.

This is it! The Reds break into Shangri-La

It was around about this time, May 1950, that I started thinking that Chamdo might possible not be the most healthy spot to stay in during an invasion, and began considering the possibility of returning to the South.

My original contract with the Tibetan Government had been for two years, and I had just renewed it. Although I was not under any obligation to stay there, I didn’t feel it possible simply to walk out and abandon the Tibetans.

My radio link was, without question, the only possible way they could get to know progress of the invasion. The only alternative would have been by mounted courier who, riding continuously day and night, stopping only to change horses, could have done it in 15 days.

In the spring however I started studying my maps and planning an emergency escape route to the south to Dzayol and across the pass into India. The plan was to use this escape route if we were cut off by the invaders.

But in July there was a devastating earthquake with its epicentre at Namche Bawa, and the whole frontier area was wrecked. We even felt the explosion and a slight rocking in Chamdo. At Loluchong on the route to Lhasa, houses were toppled and the Tibetans wagged their heads, saying: “The gods have come to help us.”

It was a 20-day march to the Indian border and a further 15 days, mostly on foot through uninhabited mountain areas, to Sadiya. News came through that the whole terrain had been altered by the earthquake. We heard the Brahmaputra had been blocked and other rivers had altered their courses. The escape plan was abandoned.

In September my good friend Lhalu, the governor, finished his tour of duty in his post and was withdrawn to Lhasa. I was sorry to see Lhalu go as he finally left with an enormous caravan and equipped with a portable radio which his successor, Ngabo, had brought with him.

Negotiator

After my capture I learned that Ngabo was one the officials sent to Peking to negotiate surrender and settlement of Tibet.

By the time October came I felt the dangers of a further advance into Chamdo and beyond by the Chinese was unlikely. Winter was advancing quickly, and it seemed unlikely that the Chinese would attempt the gruelling march to Lhasa in winter conditions.

I was right - but not quite right. As events proved, they took Chamdo in October, then lay quietly in the east and north east, and very little was heard of them until the following spring.

I doubt whether there were more than 3,000 Tibetan troops on the frontier area at the time and, judging by news that came our way, they were being confronted by a force which probably outnumbered them 100 to one.

News of small-scale clashes came from the Yangtse River area which was five days’ march away. We knew serious things were happening, but out in this territory without communications, it was almost impossible to follow developments exactly. We had only the vaguest idea of where the enemy was.

Although heavily outnumbered, the Tibetans fought courageously - fighting for the Dalai Lama. On several occasions we heard that Chinese troops had leapt into the icy river waters to escape the Tibetan soldiers.

I see that Heinrich Harrer has said in Seven Years in Tibet, which I read on my way home, that Governor Ngabo sent a message to Lhasa asking for permission to surrender Chamdo to the enemy. I was never told this and would not have known whether I had sent it, since all official traffic was coded.

But, for long, Chamdo had been a town of unrest. Tension was mounting, and the local lamas were consulted. Some monks went into the mountains for a period of solitary meditation, hoping to return with the answer to the community’s problem.

But everybody stayed put in Chamdo. There was no attempt to flee for the simple reason that for them there was really nowhere to go.

Pandemonium

One Tuesday night, late in October Ngabo had called a conference of officials to decide on a course of action. Coded messages were sent to Lhasa informing them that Chamdo was almost surrounded. The governor asked me to bring the last remaining portable transmitter if we left and asked me what transport I would require.

The next morning the little town was in pandemonium. Almost everybody who had anything was trekking up to the monastery above the town taking any valuables they had for safekeeping.

I went early to consult the governor on a course of action and discovered that he had already left even earlier that morning with a large caravan and without bothering to mention the fact to me.

I hastily put some food supplies together and with my servants hit the track northwards along the River Ngolm in pursuit of him.

I rode from morning until late evening and eventually caught up Ngabo and his large caravan. He seemed surprised to see me. I had left in a hurry, bringing a few emergency rations, a quantity of drinking chocolate, and my cameras. Everything else, including a lot of valuable equipment, we were obliged to abandon.

Around nightfall we met a messenger who had ridden from Riwoche, which is several days’ march to the north of where we were, through the most desolate terrain, averaging about 15,000-16,000 feet altitude. He told us that Riwoche had already been taken without a fight by Chinese forces sweeping down from Yushu.

This looked black and we knew from then on that the chances were that our retreat from Chamdo would be cut off.

It was bitterly cold as we continued riding, hoping to reach Lolungchung possibly by the following night. If we reached Lolungchung without meeting invading troops, according to the map, then our escape route would still be open.

About 1 a.m., in moonlight, we crossed yet another mountain pass through a biting gale that cut right through the fur-lined R.A.F. flying jacket I was wearing.

I discarded this jacket shortly before being captured since I thought the Chinese would immediately assume I was a military man in semi-disguise.

We dropped down from the pass, the ponies by this time becoming slower and slower, for we had been on the march for some 18 hours.

In the small village below, we stopped to brew some tea and eat some biscuits as we waited for some of the party, including my own servants, to catch us up. They never did, for they had lost their way over the mountain pass.

As we sat warming our hands round the steaming bowls, a messenger came in from the direction of Lolungchung, and said: “The road is cut.” So, after months of uncertainty, this was it! I must say at 1 o’clock on a bitter morning, crouching in a Tibetan mountain village, I didn’t much relish the idea either of capture by the Chinese or of decapitation by the border tribes.

For we still were not absolutely certain whether our retreat had been halted by the Chinese armies or by local Khamba tribesmen, who were known to have their own very definite ideas about running a border area and were frequently in revolt against Lhasa authority.

They had been known on numerous occasions to lop off the heads of their victims - who might be innocent travellers - first and ask questions afterwards. Finally we decided to make for the nearest monastery. If the Khambas were around, we reasoned, they would not shed blood in the monastery.

By this time we had been going continuously for nearly 24 hours, with nothing to eat but a few biscuits.

We picked up a local guide to take us to the monastery which lies near Lamda, in a beautifully wooded valley which is a riot of wild life, in grass which is waist-high. Because the Tibetan is forbidden by his religion to kill, the whole of the country is one big game preserve. The wildest-looking animals, with the possible exception of the wild yak, will continue to graze and feed as you approach them, for they have never heard a gun shot.

In the monastery we were cordially received and fed. Shortly after dawn our servants arrived - they had been on a circuitous route, fleeing from Communist troops advancing from the East.

The field was being narrowed down. Our retreat was being cut off from the East and by advancing troops from the North West.

I toyed with the idea of making a dash alone, leaving the roads and trying to hit southwards across the uncharted hills and work my way round back to the Lhasa route. But I looked at the ponies that were more exhausted than I was after 24 hours’ march, and decided that I would probably end up by being completely lost among the ice peaks.

I resigned myself to capture with the others - all of them Tibetan officials from Chamdo and their servants. Even the monks by then were becoming agitated, running round and round in near-panic, hardly able to compose themselves to prayer.

The following afternoon one young monk came running in from the valley and propelled me towards a window. My heart missed a couple of beats as I saw a column of perhaps 200 Chinese troops riding steadily up the valley, led by Khamba guides.

They carried rifles, the familiar Russian-type tommy-gun, and a type of Bren-gun. They halted a few hundred yards from the monastery, deployed, and threw a cordon round the buildings. We were surrounded.

_pthumb.jpg)